A visit to the Minotaur -- A film performance by the I-Do Lab (Ukraine)

Curated and introduced by Johannes Birringer

On December 7, 2022, a special film evening took place in the Gallery Puzić, which not only offered the opportunity to view various works by the artists currently exhibited in the new gallery, but also offered the audience an opportunity to reflect on war, art, and peace. The material offered for reflection was explosive and unusually gripping, at least in the context of the visual arts as well as the media and news transmission about the war that has been ravaging Ukraine since February 2022.

“Heimsuchen” seeking home), the German word here used for ravaging, is not a happy term of course, because the existentially fatal danger and infrastructural destruction directly and brutally affect the local people; The question of what will still be a "home" is unanswerable for the refugees. All states in Eastern and Western Europe, the governments of the EU and NATO allies who see themselves politically challenged directly or indirectly, as well as all people and organizations that want to provide humanitarian and economic aid are also being sought out, "heimgesucht," in a different way. Support for military aid for Ukraine is controversial, and moods are changeable. First of all, art is not involved in the discussion about necessary assistance or supplies for combatants and refugees, but it is also a medium of representation and of impetus, it participates politically with its means, even when it ducks (or has to duck) away, so as not to clean up the mess that it has brought upon itself.

When human rights and peace are threatened, when museums are bombed, then there is actually no question that the creative industries (as they are called in England) also get involved, that artists research and engage with audiences - whatever the noble claims of the theatre – and enter into a public dialogue. However, noble sentiments can now also be criticized in many ways in current discourses.

One has to take a stand: with this event, Gallery Puzić is opening a programmatic series with thematic focuses and interdisciplinary projects (film, music, writing, painting, performance, workshops) that will accompany the exhibition program in the coming months and years. Gallery owner Esad Puzić, himself a painter, has taken over Galerie Neuheisel, founded by Gernot Neuheisel in 1982 (and run by Benjamin Knur for the last 10 years). In June 2022, Puzić went public with a new concept for a modern art forum and began exhibiting, his stated goal being to promote diverse and more inclusive forms of expression in order to bring freelance artists, especially those with a migrant background, into the spotlight. Esad Puzić came to Saarland in the early 1990s when he had to flee the chaos of war in his home country of Bosnia, i.e. his background in life also includes an experience of ethnic/religious conflicts and ideological catastrophes that he and his family had to deal with.

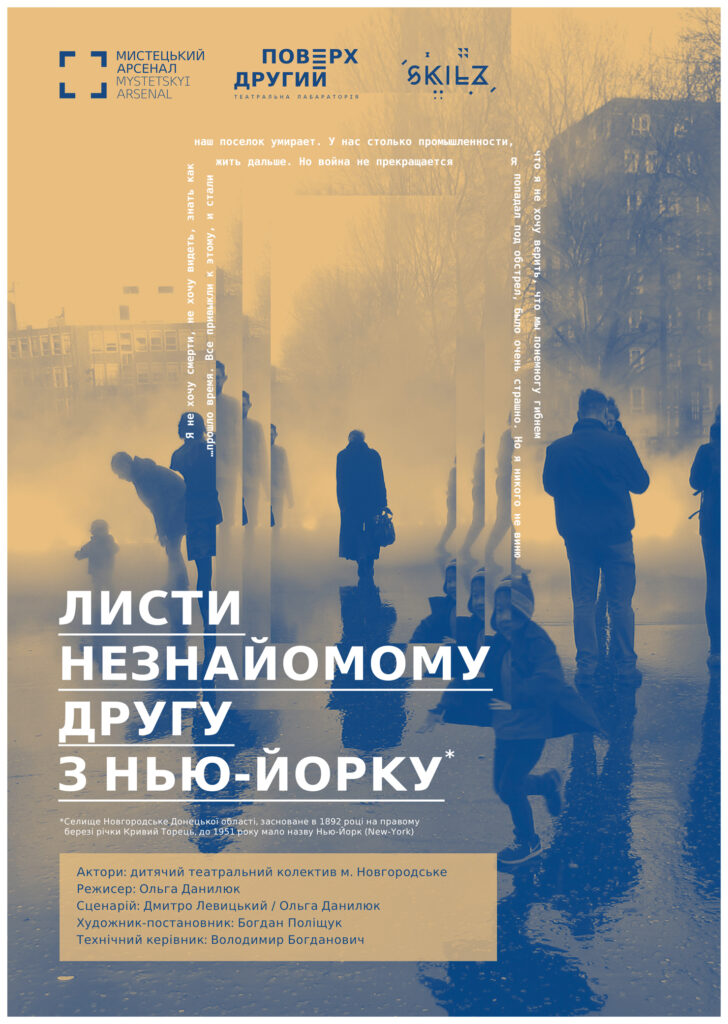

The "Visit to the Minotaur" film event reports on a catastrophe, through testimonies - spoken directly into cell phones - from predominantly young people in various cities in Ukraine: Kyiv, Kherson, Lysychansk, and New York (Novhorodske). The latter small town, located in the neighborhood of the separatist region of Donetsk, is also the connecting link, as the Ukrainian director Olga Danylyuk worked here with high school students in 2017 on an exhibition and performance about their experiences of the conflict in eastern Ukraine. The curator of the film evening, choreographer Johannes Birringer, who was born in the Saarland and lives in the USA and England, worked as an outside friend from New York (in the United States) by sending video and audio messages to the young people to encourage them and strengthen their resilience.

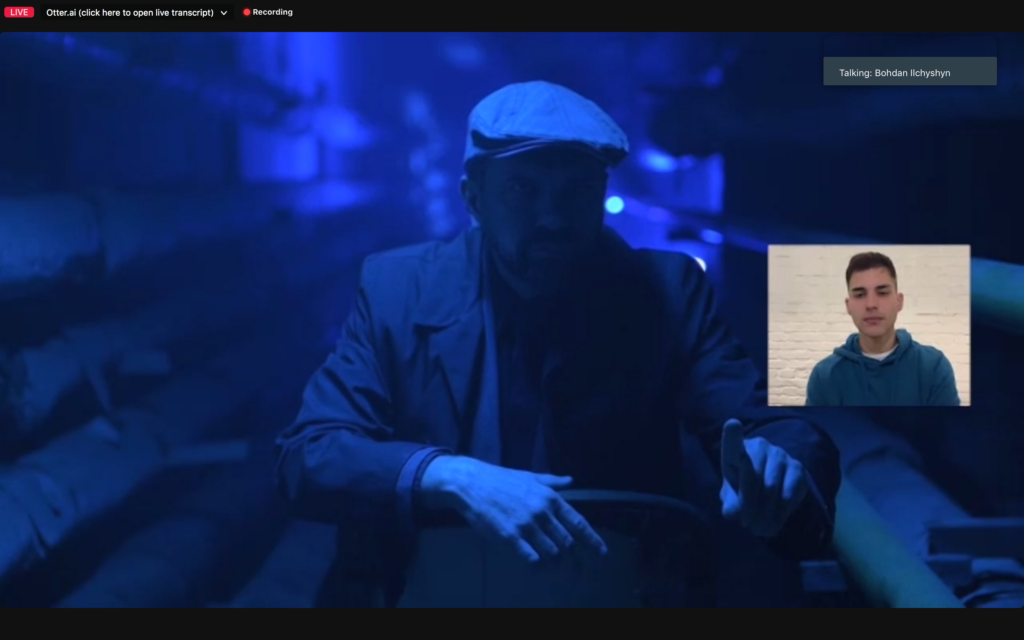

After years of contact with Danylyuk, Birringer was asked to take part again in autumn 2022 and was informed that the Kyiv-based director, who had also continued her theatre research in London, was preparing a new production with her artist group I-Do Lab. Live streamed (live from Kyiv) at London's Cockpit Theater on November 3rd, "A Visit to the Minotaur" combines witness statements, original videos and photos provided for the project, and documentary evidence from social media – all directly related to deeply moving personal experiences, especially of young people in Ukraine, during the first days, weeks and months of the outbreak of war.

With new German subtitles, the film "A Visit to the Minotaur," which is now being presented for the first time in Germany at the Gallery Puzić in Saarbrücken, can be described as a documentary performance that, like no other, tells authentic first-person stories directly from war-torn Ukraine.

The performance connects viewers virtually with real people who are suddenly surprised and caught up in the war. Viewers are invited into houses, rooms, underground shelters. Once you enter the Minotaur's labyrinth, your life is in constant danger. No one knows when the final goodbye will come... a shopping trip turns into a trip to the trenches, an escape to grandma's house leads to a month in hell, a missed evacuation saves your life. A mother is faced with the most difficult decision: which of her disabled children will she take on a secret journey out of occupied territory? This cannot be true and real. The world seems to be going crazy. But there is still hope: maybe it is possible to wake up and everything will be as usual? But the nightmare is reality and the Minotaur is about to claim his next victim.

In his introduction to the work of Olga Danylyuk and their association, Birringer projects a few silent images into the room: a photo of the Chanenko Museum in Kyiv, which shows cleaning women sweeping up the shards of the broken windows, a few illustrations from the “Diary from Kiev” by Sergiy Maidukov, as well as a sculpture (“Minotaur”) from the series “The Wrath of Achilles” by the Ukrainian sculptor Volodymyr Ivanov, who is also present in the Gallery on that evening.

A map of the attacked and occupied areas of Ukraine is also shown, as well as a commentary by the sculptor Ivanov coupled with a quote from the director, both of which are reproduced here.

~~~

The war turns everything upside down.

First and foremost, it's about our perception of the world.

The local and the global suddenly swap places.

What seemed private, local and measurable yesterday suddenly sounds loud, shrill,

and reveals an epic connection to processes on a planetary scale.

Volodymyr Ivanov

~~~

~~~

“Наші люди міцніше за сталь" - “Our people are stronger than steel”,

they say in Donbass. But - what does that mean for kids and teenagers who saw their innocence and hopes shattered by the Donbass conflict?

In “Listi незнайому другу з Нью-Йорка – Letters to an unknown friend from New York”, 13 teenagers from Novhorodske (New York) tell their stories with honesty and simplicity. They talk and sing about present times and imagined futures.

Olga Danylyuk

(Letters to an Unknown Friend in New York, 2017)

Olga Danylyuk

(Letters to an Unknown Friend in New York, 2017)

~~~

After the film screening, the painter/film dramaturge Uschi Schmidt Lenhard and Johannes Birringer led the discussion with the audience and asked for reactions to the production. At first you could tell that the well-filled gallery space had fallen silent. A certain heaviness weighed on everyone – the eyewitness reports and memories of the women and young people affected were raw and undisguised, hardly accompanied by images from social media, nothing distracted from the faces in the film, although there was once a sequence of a drive through a destroyed suburb while the Kiev woman Oksana talks about how she looked for food in empty houses because there had been no food for the children for days. At some point there are also surreal, shadowy shots of a Russian helicopter attack - black birds soaring in the sky, filmed with a shaking hand.

But mainly only the voices of individual people reached us, face to face with the camera, with the typical vertical image section of the cell phone. Voices that sometimes spoke quickly and hastily, as if breathless, but then also thoughtfully searched for fragments of memories and put them together like a puzzle. Or halting, struggling to breathe. Holding back tears. Bursting into desperate laughter at the mad search for a cat that went missing during the first bomb scare.

Should a warning leaflet have been distributed that evening, as is now more often the case in German theatres, to warn of risks and side effects? “This production contains explicit narrative depictions of physical, military, psychological and sexual violence, which can have a stressful or retraumatizing effect.”

The warning was certainly not necessary, but the audience also quickly noticed that one cannot speak simply or naïvely about war, or even about the desire for peace, that one cannot only emotionally admit, reflect on or describe one's concern intellectually, but rather that it would also be important first of all to want to understand and assimilate what is being told - this particular kind of "Heimsuchung" (visitation)? Descriptions or sketches seem helpless at first, but they may be important.

They are indeed very different stories and can be received in different ways. Sometimes everyday little worries and banalities (where can I buy groceries, did grandmother pack the medicine, can I run a bath to relax, why does the lecturer annoy me in the lecture, why does father stand in the garden and look at the sky in disbelief – where no angels are visible) alternate with dramatic and sudden images of horror.

And the editing of the film also speaks a fluid, sometimes idiosyncratically rhythmic language, the names and places appear choppy like a machete, people talk about rockets and checkpoints, broken equipment on the streets, holes in walls and stockings, the taste of condensed milk, interrupted again and again by the mythical-political figure of the Minotaur, who patiently waits for his victims in the air raid shelter.

This waiting is a horrible provocation, portrayed by a male actor who, in the film, comes towards us (as a screen) and presses on the screen mirror to call up the witnesses. It's an eerie cinematic reference to Steven Spielberg's sci-fi thriller "Minority Report," in which fortune tellers - the Precogs - foresee future crimes in their visions in order to pass on this foreknowledge to the investigators.

"A Visit to the Minotaur" puts the precognitive criminal fiction into the shadow, because here young people actually convey stories of their bewilderment and initial disbelief that a war could have become a reality, that the possible had simply been repressed as non-possibility, and even repression continues to function during the first weeks of the war or is converted and adapted into a different type of acceptance. Reality is reality in the here and now, you learn to distinguish the different sounds and tones of rockets and mortars. Glass splinters are swept aside. The paintings have been taken down and brought to safety in the Chanenko Museum in Kyiv. Only the signs on the walls reveal which picture was hanging here.

In her moderation, Schmidt Lenhard seriously pointed out the pacifist approach and her unwavering belief in the reason of peace. We must all hold on to this: war has never been a solution. Judging by the behavior of the predominantly local audience, many agreed with the desire for peace, understandably, but sculptor Ivanov strongly disagreed. Not only could he confirm the young people's descriptions in the film; he also didn't want to go into the horror scenarios of the war or, for example, the destruction of Mariupul, but for Ukrainians, he pointed out, only victory counts as the end of the war. The anger of Achilles resonated in Ivanov's trembling voice, and one can imagine what he meant with his steel works of art with references to mythical echoes from the history of European catastrophes (including their unspeakable founding myths).

In a conversation with Ivanov, it later turns out that he himself was surprised by the course of history: The series “Wrath of Achilles” was created 30 years ago using Saarland steel, then 15 years later it was exhibited on the rocks of the Black Sea island of Zmiinyi (Snake Island). and then landed in the halls of the UN Palace in Geneva. Another 15 years later, the sculptures return to the Saarland with the mission of thanking them for their contribution to the defense of freedom and European values (as it says on Ivanov's website).

These values are questionable, just as silence and anger point to our necessary cognitive dissonances. An observer from Switzerland, the literary scholar Heiner Weidmann, commented on the discussion as follows: Two things didn't really work for him - firstly, the speechlessness, the overwhelming lack of a discussion. Why should it be that you simply can't say anything more about X – and especially if X is not simply a Factum brutum, but a film (an artwork) generated through numerous formal decisions, and even things (facts), even if they offer an impenetrable surface in their perfection or horror or beauty, can they not be mechanically exploded or chemically dissolved through thought? So that the solidity is gone and the inner tensions explode?

Or is it perhaps related to the second point, asks Weidmann – not peace, but victory. That is, it is not real horror to see the images of war, but rather a cause for hatred, a motivation for war against it, which this time is a just, unavoidable one. Perhaps the staging of the Minotaur myth resulted in an aestheticization of war (from the victim side), which makes it as grandiose as a natural disaster (and makes you forget that on the other side of the front there are also cellars and corridors with victims and survivors inside). Here, Weidmann touches on a very sore point, which Schmidt Lenhard probably also implies: Ukrainians are dying, but young Russian people are also dying, whose families are perhaps largely left in the dark by propaganda about who is dying for what.

Weidmann adds resignedly that since Russia was much less well-equipped militarily than the annual parades on Red Square suggested, and since Russia had weaknesses on the battlefield, it may now seem unreasonable to negotiate (before the most favorable “facts have been established”) a peace. And the fact that it is a forced war, a war of aggression, makes the biggest opponents of the war silent. And if Ukrainians don't find the war, at least theirs, pointless, who can stop them from being pro-war? And the film showed the audience not the futility of war, but rather the evil and depravity of the attack. The anger of Achilles, Weidmann points out, is actually the anger over the death of his beloved friend Patroclus, which drives Achilles, who had gone on strike and refused military service, back into battle, angry and raging and thereby bringing about the victory of the Greeks, just as he could not have done as a mere participant in the war.

"A Visit to the Minotaur" does not show this anger but keeps it hidden, the young people, daughters, granddaughters, and mothers talk about decisions that have to be made, escape, staying there, helping neighbors, worry, precautionary measures, etc. Meanwhile, in the southeast of Ukraine, in Russia-occupied Mariupol, a grotesque spectacle of a reanimated Stalinist cultural policy is taking place, namely the construction of a huge Potemkin façade ordered by the occupiers, which serves as a screen with painted portraits of great poets (Pushkin, Tolstoy, Gogol, Shevchenko) in front of the ruins of the completely destroyed city Theatre. Perhaps it is the weakness of art that it can be instrumentalized in so many different ways, which at the same time does not detract from its importance, but rather confirms its grotesquely disproportionate value in our societies.

Film credits:

Wednesday, December 7th 2022, 7:00 p.m

„Besuch beim Minotauros“

A film performance by the I-Do Lab (Ukraine)

Director: Olga Danylyuk Olga Danylyuk

Mitwirkende: Featuring: Karina Varfolomeeva, Milena Medvid, Lisa Podgaiko, Oxana Avramenko, Michael Onyshko, Anatoliy Zavorotniy, Esmira Gasanova.

Artistic collaboration: Roman Grygoriv (music), Bogdan Ilchishin (video design). Fedir Aleksandrovych (graphics), Richard Danylyuk (subtitles in English/translation), Oleksiy Musika (stream), Johannes Birringer (voice over/subtitles in German/translation).

Zeitungsartikel: Saarbrücker Zeitung